- Home

- Leisel Jones

Body Lengths

Body Lengths Read online

Published by Nero,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

37–39 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

[email protected]

www.nerobooks.com

Copyright © Leisel Jones and Felicity McLean 2015

Leisel Jones and Felicity McLean assert their right to be known as the authors of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Jones, Leisel, author.

Body lengths / Leisel Jones with Felicity McLean.

9781863957267 (paperback)

9781925203172 (ebook)

Jones, Leisel.

Swimmers—Australia—Biography.

Women swimmers—Australia—Biography.

Olympic athletes—Australia—Biography.

Women Olympic athletes—Australia—Biography.

McLean, Felicity, author.

797.21092

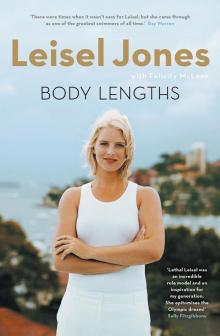

Cover photo by Hugh Stewart

Cover design by Peter Long

Text design by Tristan Main

Contents

Prologue

1. Fish out of Water

2. First Splash

3. The Big Dawgs

4. This Baby’s Going to the Olympics

5. Rookie

6. Sydney 2000

7. Training for Gold

8. Under Pressure

9. Stilnox Days

Picture Section 1

10. Olympic Lies

11. A New Start

12. Starving to Swim

13. Aussie, Aussie, Aussie!

14. Commonwealth Triumph

15. Blast from the Past

16. Matters of the Heart

17. Taking Risks

18. Crashing

19. Beijing Blues

Picture Section 2

20. Relief

21. Fallout

22. The Lonely Days

23. Opening Up

24. The Depths in the Heights

25. The Comedown

26. London Calling

27. Toxic Team

28. Breaking Point

29. My Way

30. Back on Dry Land

Acknowledgements

This book is dedicated to all the people out there with big hearts and even bigger dreams. Anything is possible if you are brave enough to go out and grab life by the balls.

– Leisel Jones

For Andy

– Felicity McLean

Prologue

In the darkness you can’t see the mountains on the horizon, skulking beneath their snowy peaks. The running track with its neat lines is swallowed up by the night. And the structure we call the James Bond tower, with its strange wires and tall aerials pointing accusingly at the sky, stands in shadow.

Sierra Nevada is purple-black tonight, the colour of blood before the air gets to it. Oxygen is scarcer at this altitude, 2300 metres above sea level. Even the sky cannot breathe up here. Even the sky seems to bleed.

I leave the centre at 4 a.m. I don’t say goodbye to anyone; I just walk outside to where the van is waiting for me, climb in, nod to the driver and wait for him to take me away.

We drive on and on in the dark. Morning never seems to arrive. Am I dead? Did I do it? I wonder. But then the airport rears up before us and I can make out the shiny lettering – ‘Aeropuerto de Málaga – Costa del Sol’ – so dawn must be arriving after all.

On the plane I can’t figure out how I got here. Did I check in? Did someone scan my passport? (Name: Lethal Leisel; Occupation: Swimmer). I can’t remember any of this. I want to call Lisa to ask how I got to this point … but there’s plenty of time. I will phone her from Singapore, then again from Sydney, and from Tullamarine in Melbourne. Reporting for duty, keeping in touch, letting her know I am still alive.

Am I still alive? I have to look at my wrists to make sure. They’re slick and smooth from a lifetime of chlorine and sweat. Strange to think they nearly looked so very different.

I think about my dad. He won’t be waiting for me to call from the airport. We haven’t spoken since the day he walked out on Mum and me, thirteen years ago. Up until last year, I was still pretty angry with him. A lot of people have issues with their fathers, I know. But not everyone’s dad goes to the press to tell their daughter they are dying of cancer. I mean, really. I can’t forgive that. What a disgusting way to give your daughter the news. It was so embarrassing – so humiliating – to have our relationship blasted all over the papers. But now I’ve reached something like forgiveness. It sounds wanky, but on a deep level I’ve gone: Okay, you probably did the best you could as a dad. It was a shit job, but it was the best he could do, and I’ve made peace with that. I’m sure his father was crap too. Whatever.

But now I find myself wondering if my father’s dead. Did the cancer get him in the end? Something else, maybe? I wouldn’t know. And I honestly don’t care: he’s dead to me already.

Lots of friends have said, ‘Oh, but you’ll regret it when he dies.’ Regret what? He deserted us. He left us bankrupt. I’m not the one with something to regret. Why should I have to meet him? It would make me feel icky and gross. Why should I go through that?

I’ve always been really strong in doing what’s right for me. That’s one thing I’m proud of: if it doesn’t feel right, I won’t do it. And it feels right for me not to connect with my father. I’m not holding on to anything. I’m not angry. If I was, then yes, I should meet him and talk to him. But I’m not angry or bitter. I’m not anything, in fact.

Now, wondering whether he’s dead, I realise it wouldn’t make any difference if he was. His actual death wouldn’t matter.

Does anyone’s? Does anyone’s death make any difference? Would mine?

I spent yesterday afternoon on the bathroom floor of my room at the Sierra Nevada high-performance sports centre, planning to kill myself. While the rest of the Aussie swimming team ate, talked, kicked a ball or watched TV, I thought about slitting my wrists. And my legs – I didn’t forget my freakish, talented legs. I’d decided I would be leaving that place in a body bag.

I stare out the window at the clouds and picture myself inside the bag, as I have a thousand times already this week. I see the zipper close, the last ray of light disappearing. I am lost again in the dark, in my pain …

It’s yesterday, a bone-dull afternoon, and I’m back in the bathroom, staring at my wrists.

I am going to do it: I am so clear. I have saved up some sleeping tablets and I will take them all. A knife from the kitchen will do the rest: I’ll slit my wrists, slash my legs, make sure I get all the big veins. I’ve even googled how much it would cost to send a body bag home from Spain. It’s $15,000 or something like that – pretty expensive – but I’ve checked that there will be enough money left for Mum to pay for it.

I am determined; I know what I have to do.

I have the afternoon off training, so here I am in the bathroom preparing. I can do this. I’ll take the pills first, and then I’ll just cut. I’ll cut them all open – my legs, my wrists – so I bleed out.

I will slice myself open and bleed purple-black like the Sierra Nevada night sky.

1

Fish out of Water

In the hospital where I am born, I am the only white baby. In 1985, in our mostly Indigenous community in Central Australia, there aren’t many outsiders, let alone fair-skinned ones. In Katherine District Hospital, from the instant I take my first gasping lungfuls of

oxygen, I am a fish out of water.

‘Leisel?’ asks the doctor.

‘Leisel,’ Mum says firmly. If I have to be stuck with ‘Jones’, Mum’s not having a bar of ‘Sarah’ or ‘Jane’ or any such unremarkable name to go with it.

‘You can’t call her Leisel,’ says the doctor, as if the question of my name is a medical one, as if his opinion is somehow warranted. ‘It’s not a real name.’

‘It is a real name, and you might not know it yet, but “Leisel Jones” is a name you will remember,’ Mum says prophetically.

Mine would have been a difficult birth, a breech birth – I try to exit the pelvis feet-first rather than head-first – but I am eventually born by caesarean. For a few moments after birth, I stop breathing and need to be resuscitated. A fish on a hook, I gulp for air.

Katherine, where I am born, is known as ‘the crossroads of the outback’. It’s almost 300 kilometres to the coastline in any direction, except to the formidable south, where the coast is even further away, beyond the Tanami and Simpson deserts, the two largest deserts in Australia. It’s only twenty-four hours from Katherine to the geographical centre of Australia. Less than that to Uluru. There’s spinifex and red dust as far as the eye can see; nearby gorges are so deep you might never find the bottom.

Life in Katherine, for the first six months of my life, is simple. Basic. My parents are travelling around Australia in a double-decker bus and my two older half-brothers are doing School of the Air. The plan is to save a bit of money, do things a bit differently. In the first months of my life I breathe in red dust and my mother bathes me in the kitchen sink.

Then one day Mum and Dad fire up the bus and hit the road again, back to New South Wales. Back ‘home’. Mum’s parents, my Nanna and Poppa, live on St Huberts Island, which is a couple of hours north of Sydney, on the Central Coast, so it’s a homecoming of sorts. On St Huberts Island we live a more ‘normal’ family life: barbecues, playing in the park, visiting nearby Umina Beach with me as a toddler on the back of Mum’s bike.

Except the normality doesn’t last long: after two years, suddenly we’re on the move again, but this time we’re headed north. To Queensland. Wamuran, to be precise. A small scrap of a town, 11 kilometres west of Caboolture and an hour north of Brisbane. A scrap of a town for a scrap of a girl. We live beside 300 acres of vacant land – disused scrub. We don’t own the land – could never afford to own all that – but we build a house on Alexandra Parade that backs on to the land and we pretend all 300 acres of it is ours.

So now this former ‘outback’ girl is a ‘country’ girl.

Not much water in this story so far, is there?

Well, that’s not quite true. We have a creek on ‘our’ property in Wamuran, and a massive dam too. There’s a rope swing with an old tyre, and we spend long arvos yabbying. There’s even a backyard pool. But I don’t do too much swimming yet. Sure, I take lessons, just like most other Aussie kids: ‘learn to swim’ classes to keep me safe in the water. Mum takes me once a week. Outside of lessons, however, I’m not that interested yet.

I am not a sporty kid. Active, sure; outdoorsy, yes; but not typically sporty – not in the way you see some primary school kids picking up ribbons every time they turn around. I do gymnastics, but Mum laughs about it, because I cannot, for the love of god, stay on the beam. And at netball, I’m always the last to be picked for the team. At tennis, whatever I lack in talent I make up for with talk. (‘Leisel could do better if she talked less and concentrated more’; ‘Leisel must try hard to stop distracting others’ – just once I would like to get a report card that doesn’t say these things.)

I’m not much of a runner, but when my dog, Jedda, is bitten by a red-bellied black snake, I run bloody fast.

And I do ride horses. I have a horse called Gypsy that Mum saved from the knackery. I ride him bareback, and when he kicks me off I get straight back on. He might be stubborn for a horse, but I’m a mule.

Sporting prowess doesn’t run in my blood. Mine is a diverse, creative family. There are artists and inventors, as well as normal people with normal jobs, but not a lot of sports heroes kicking around. There are no amazing sporting genes for me to inherit.

But me and the two boys from down the street, we have competitions all the time, tearing down the big hill on our cheap imitation BMXs, turning at the last second to save our scrawny necks, sliding and skidding to a halt. Riding our bikes down the face of that hill on Alexandra Parade, the boys and I are far from average. We fight it out for BMX glory. A girl in our street came off her bike on that hill once and was picking gravel out of her face for a week. That never happens to us. We’re daredevils – gung-ho – the three of us.

So I guess I am sporty enough to stay on that bike.

We spend every arvo after school mucking around outside. We compete to see who can ride the fastest, who can skid the furthest and who can get the most air off a jump. We have competitions of every kind, me and the boys down the road, but strangely we never think to race each other in the pool. We don’t get in it much at all, really.

Then one day it’s all gone. The house. The 300 acres. Even the pool I haven’t swum in much yet.

I am watching TV when Mum gives me the news that Dad’s off. It’s my favourite show: Get Smart, with the bumbling Maxwell Smart and the ever-patient Agent 99. I know it off by heart: the ‘old phone-in-the-shoe trick’, the KAOS villains. I walk around the house quoting, ‘Missed it by that much!’

During an ad break, Mum walks in. ‘Dad’s leaving,’ she says. ‘We’ve run out of money.’

I say nothing. I just sit silently and wait for the ads to finish.

Dad doesn’t come into the TV room to find me. He doesn’t tell me himself. In fact, I never see my father again. He has gone by the time Mum tells me he is leaving.

Missed it by that much. What a coward.

Even before he took off without telling me, my dad was never a man of many words. My name, Leisel, is an anagram of his name: Leslie. Mum chose it for that reason. I was also due to be born on Dad’s birthday. But because I was to be a caesarean birth, Mum was able to choose to have the surgery a day later so that Dad and I could each have our own birthday. Even so, with our almost-matching names and our almost-matching birthdays, surely we were meant to be kindred spirits. A real chip off the old block, that’s what I was meant to be.

Funny, then, that it didn’t turn out that way. We are both tall and strong, but Dad is quiet, whereas I’m a talker. From a young age, I’m full of life, Mum tells me, and full of words. I have so much bubbling up inside me, whereas Dad has … what? Nothing? Absence?

It’s easiest to describe my dad in terms of what he isn’t. I’ve started racing in local swimming carnivals by this time. But Dad isn’t a sports dad who rages, threatens and intimidates from the sidelines. Dad never bullies my rivals. He isn’t the kind of swimming father who nearly has a heart attack on the pool deck, living each lap as if it were him in the water slogging it out, not his kid. Nor is he one of those sad, bitter fathers you see at kids’ sports events, flogging his children as some sort of penance for his own childhood defeats. He isn’t even one of those greedy professional sporting parents who make the headlines for syphoning money from their kid’s trust account. Dad isn’t any of these things – because he isn’t there. He never comes to watch me swim, never once takes me to training. Dad never shows up to my swimming carnivals. He never supports me, doesn’t show any interest in me. Sometimes I wonder if he cares at all.

There was one day, though, when Dad cared about something – a day when Dad was actually excited …

I was ten when Dad bought the business that was going to set us up good. It was a plumbing business, a real money-maker. ‘We’re laughing now,’ he told us, ‘all the way to the bank.’ We went down to the warehouse to admire and coo, me and Mum, with Dad leading the way. We poked around the big old barn of a warehouse. We were laughing, all of us. All the way to the bank.

Only it di

dn’t work out like that: not like that at all. Dad never made any money, only lost it slowly.

Then all of a sudden he was losing it fast. We were bankrupt. Insolvent. And no-one was laughing. We went to the bank but no-one was chuckling. The business was gone, and Dad was off. The house was repossessed soon after.

The last time I see my father, I am twelve years old.

When Dad leaves, Mum and I stay on in the house together, reigning over our scrubby acreage, until the Christmas school holidays – as long as we can afford. Mum is working as a swimming teacher and somehow magics food onto our plates each night. It’s breadline territory stuff: minute steak and cheap spuds, pork shoulder when it’s on special, curried sausages and vegies. But it all tastes good to me. Wouldn’t most kids be happy to live on curried sausages? Don’t most kids have breadline tastebuds anyway? Maybe I’m not so different after all.

But I’m stranger than you might think. When I was seven, my parents drove me to Brisbane to see a paediatric surgeon, because I have a congenital abnormality, a freakish glitch. I was born with a twisted hip. It’s nothing serious. There’s no prolonged damage being inflicted on my body or anything like that. But I am noticeably knock-kneed, and this causes me terrible, excruciating embarrassment in the school playground.

‘Please do something,’ I beg my parents. ‘Can’t we get a doctor to fix me?’

Inside his plush surgery, the orthopaedic paediatrician smiles generously at my unsuspecting parents. ‘Sure, we can correct this,’ he says. ‘It’s just a glitch.’ Then he slides a piece of paper across the wide, mahogany desk.

In 1992 in Queensland, ‘correction’ means surgery. It means breaking and re-setting my right hip; it meant casts and traction and all sorts of barbaric-sounding stuff. I don’t care. I am desperate. I would give anything to walk across the stage at school assemblies with straight legs, to step onto a netball court without my knock-knees on display beneath my navy blue netball skirt … I would break my legs myself for that.

Body Lengths

Body Lengths